"I felt chained to the floor for the last three years," he says, but he did ultimately begin work on new music with his band of brothers in Queens of the Stone Age.

But Brubeck didn’t make such lofty claims himself-he followed his imagination and arrived at a sound that was thoroughly his own.His work as a creative artist slowed to a crawl during that time, he says now. It’s a narrative with more than a hint of white saviorism, and it looks especially silly in light of all the other jazz innovation occurring in 1959. Steve Race’s original Time Out liner notes slip at times into reductive overpraise of the Brubeck quartet as somehow singlehandedly keeping jazz rhythm interesting.

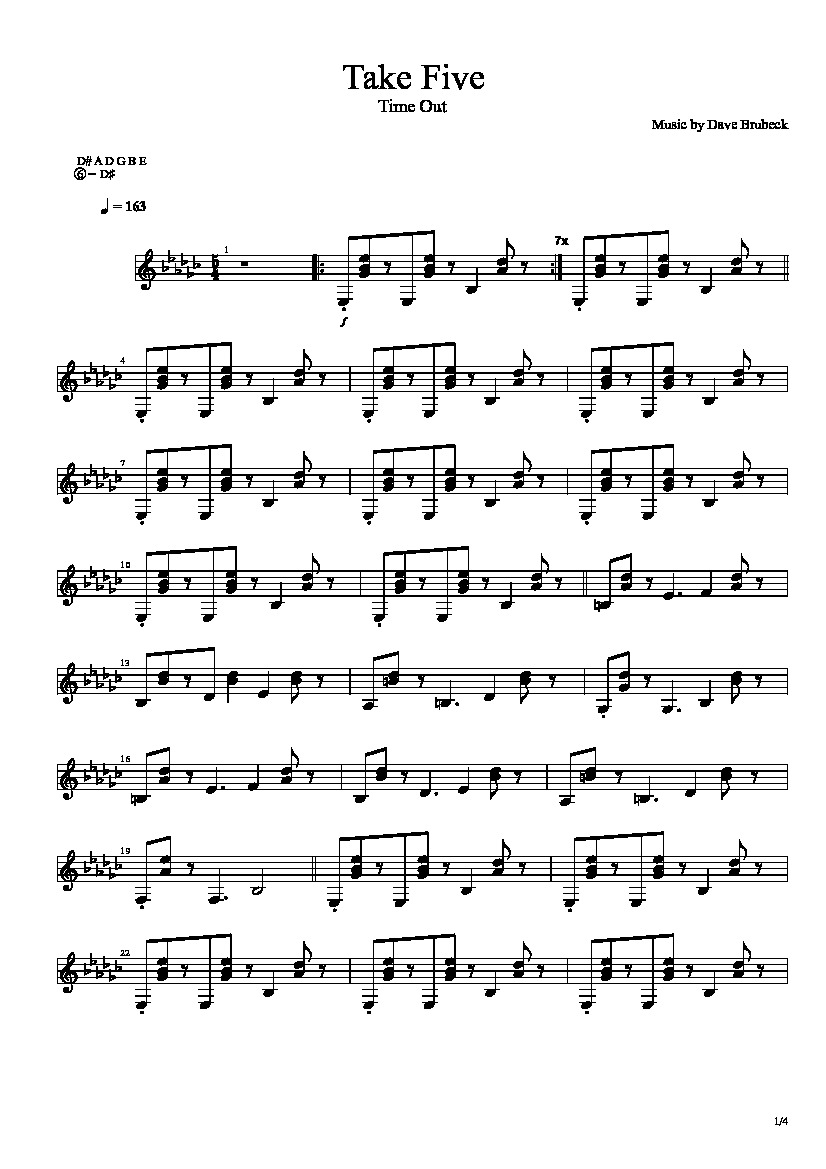

“Everybody’s Jumpin’” is fetching as well, with its sleek modernist glide (Brubeck and his lyricist wife Iola soon reworked the song as “Everybody’s Comin’,” the lively opening number of The Real Ambassadors, their satirical musical revue on the topic of jazz and Cold War diplomacy). “Three to Get Ready,” “Kathy’s Waltz,” and “Pick Up Sticks” are built on well-crafted rhythmic conceits that prompt solid performances across the board. “Strange Meadow Lark” has a beautiful out-of-tempo piano intro and a goosebump-worthy Desmond entrance. There is also more to Time Out than “Take Five” and “Blue Rondo a la Turk,” the blockbuster tracks. That Desmond alto, underscored by Morello’s brushes on snare drum, remains one of the most identifiable sounds in jazz. So does Desmond, whose boundlessly lyrical, almost clarinet-like alto sax improvisations epitomized the softer timbre and relaxed vibe of West Coast jazz. His approach was eclipsed by the lithe modernism of McCoy Tyner, Chick Corea, and Herbie Hancock, but in terms of musical content and personality, Brubeck stands the test of time. Brubeck’s piano was steeped in blues and had a palpable connection to stomp, boogie-woogie, and earlier jazz styles. Yet the quartet exhibited a developed sense of swing thanks to bassist Eugene Wright and drummer Joe Morello.

The fast and asymmetrical pulse of “Blue Rondo a la Turk,” the opening track, bore traces of Balkan and Turkish influence. The impetus for the rhythms of Time Out came in part from Western classical music, in part from the band’s travels in India, the Middle East, and elsewhere. Yet as avant-garde cornetist Taylor Ho Bynum wrote in The New Yorker shortly after Brubeck’s death in 2012, “Those musicians, too hip for their own good, who dismiss Brubeck as square do so at their own loss.” Time Out and the rest of the quartet’s “time” concept albums ( Time Further Out, Time Changes, Countdown: Time in Outer Space, Time In) merit close attention as some of the most engaging and unique small-group jazz of the era. 2 on the Billboard pop charts, but it also yielded jazz’s best-selling single of all time: “Take Five.” Written by alto saxophonist Paul Desmond, the tune had a novel 5/4 groove but ultimately came to be identified with a kind of inoffensive hotel lounge jazz. Time Out, his 1959 foray into odd time signatures, polyrhythm, and mixed meter, not only ended up going platinum and reaching No. It’s ironic that in Dave Brubeck’s attempt to make jazz more complex, he actually made it more accessible.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)